September 2019

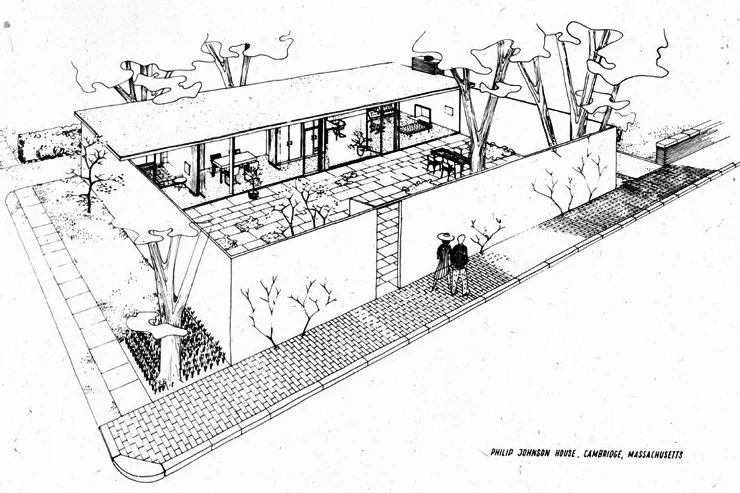

9 Ash Street Perspective, Philip Johnson, Cambridge c.1942 [1]

As I delve into architectural theory, the more I have began to recognise that moments of disruption in the architectural discourse are marked by a built outcome. These projects sit as a tangible culmination of years of research and ideas. They exist as beacons throughout the architectural timeline - standing not just as buildings, but crucial pieces of architectural theory that can influence subsequent generations.

These built outcomes stand as a thesis for the architect’s ideas. They are usually perfectly timed in the architect’s career, for a well-timed client. Thankfully there are numerous key examples of these buildings that I have started calling ‘Thesis Houses’. Since my realisation of their existence, my travels have actively tried to track them down to inspire my own thoughts. This post will explore several key Thesis Houses and highlight their importance.

The greatest theoretical ideas remain as theory until they are realised. As I discussed in my previous post on I.M. Pei, the Modernism movement swept the world in the early 20th century. The ambitious ideas aimed to disrupt the classical norms through breaking free of traditional mandates. These early ideas only began to gain international traction when the first series of built outcomes started to be published around the world. Most notably the early International Style projects of Le Corbusier. These projects allowed the theories of modernism to develop a critical mass and eventually became the leading contemporary theory of the next generation.

Model of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye from ‘Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, MoMA, 1932 [2]

Philip Johnson’s path to architecture was not a traditional one. Johnson had difficulty clarifying a career direction for his passions and meandered through pursuits of politics and international travel in his early years. Johnson well before any formal architectural education became inspired by modernist architecture and travelled extensively to Europe documenting early modernist projects. His pursuits sought out these inaugural projects and formailised their standing as the Thesis Houses of the modernist movement in the MoMA exhibition ‘Modern Architecture: International Exhibition’ in 1932 - which Johnson produced in collaboration with Henry Russell Hitchcock.

Johnsons career had started with a deep exploration into the theory of design and the exploration of the physical conclusions of these concepts. With this grounding he decided to leave his role at the Museum of Modern Art and study at Harvard, to eventually leave several of his own Thesis Buildings on the architectural landscape.

9 Ash Street Plan, Philip Johnson, Cambridge c.1942 [3]

Johnson came to Harvard in a unique position as a wealthy, mature aged student, with his own publication from MoMA on the syllabus at Harvard. He utilised the resources at Harvard to develop an immense repository of architectural aesthetic and theoretical knowledge. This was a skillset that he continued to grow and utilise throughout his career. For his thesis at Harvard, Johnson was able to create a literal Thesis House. At 9 Ash Street in Cambridge, completed in 1942, Johnson executed one of the earlier International Style dwellings in the US. This house was a realisation of all that he had studied. It gave not only Johnson, but the International Style a built form to market and grow from.

The house is framed by a 9-foot-high wall, that runs around the full boundary of the Cambridge site. Within these private walls, in a very Miesian style, sits a large courtyard and small single bedroom open pavilion that foretold his future efforts at the Glass House. Johnson lived in the house after its completion. His own Thesis House became a gathering point for the architecture social circles that continued to push the boundaries of design ideas.

The strength of Johnson’s career lay not in his own native architectural genius, but in his understanding of style trends and his ability to make the new styles his own. I doubt there has ever been an architect who utilised the Thesis House more readily throughout his career. As each contemporary design style evolved, there was Johnson, out front with a built resolution of these concepts that could be the flagship building for each moment in the architectural timeline.

Ash Street as a marker for the International Style; the Glass House as the icon of Modernism; and the AT&T Building as the poster boy for Postmodernism

Trenton Bath House, Louis Kahn, Trenton c.1955 [4]

I use the term ‘house’ in Thesis House quite loosely. The ability to realise a varied stream of thoughts into a static built form can be quite challenging – especially when these concepts are as abstract as Louis Kahn’s. The inherent complexity of trying to extrapolate a built form from an innovative stream of ideas, naturally prompts a smaller project, where the difficulties of brief, budget and site are less challenging. This usually leads to these foundational projects being realised as houses for an understanding client, or in Kahn’s case a small bathhouse project in Trenton, New Jersey c.1955.

Kahn stands as one of the most iconic architectural figures of the 20th century, and as you can see from his prominence in my own writings, someone whose work and theories have had a great impact on my own architectural development. Kahn’s early career was pretty unremarkable with numerous projects opening to varied levels of success. Kahn was struggling to resolve his desires for human focused, monumental forms. His earlier attempts, such as the Richards Medical Research building at The University of Pennsylvania, show clear signs of Kahn’s unique ability to understand materials and spatial sophistication. This project disappointingly is inherently cluttered and confusing to both the eye and the occupants.

Richards Medical Research Laboratories, Louis Kahn, Philadelphia, c.1965 [5]

It wasn’t until Kahn went on a study of ancient Europe that he was able to refine his concepts with the introduction of increased geometric monumentality. Kahn was able to develop the understanding that if he could maintain both the importance of occupant experience and honesty of materials, and then couple this with the monumentality of the classical forms, he may be able to realize the desires of his long stream of ideas.

Kahn freshly inspired by this new sense of comprehension was able to test them on the Trenton Bath House project for the Jewish Community Centers program. The bathhouse design strips away the disorder of his earlier buildings and instead creates a monumental form made of everyday materials in a sophisticated manner. The brief was simple, but still allowed enough scope for Kahn to playfully interlock the functions together. Kahn utilized the corners of the four pyramid shaped roofs as strong buttresses that anchored each form together, as well as providing areas for the services and storage to be hidden away.

Trenton Bath House Plan, Louis Kahn, Trenton c.1955 [6]

This project marked a substantial moment in his career. For the first time Kahn was able to realize holistically his architectural ideals. Whilst the project may seem simple and modest, it was exactly this fact that allowed Kahn to marry together several streams of consciousness in a successful manner, which he had not done before. This project gave Kahn the confidence to pursue these notions with new vigour and execute them at much larger scales and with far more complex briefs.

“To prevent things from being done in an ugly manner, or in a manner which tends to deteriorate the original motives, our principles must be so true and real that they cannot be easily destroyed.”

Kahn’s Thesis House came much later in his career, at a point where his flailing ideals had been allowed to grow enough that a moment of clarity could be found. These projects can happen at any point along the career of an architect. Some find this moment of clearness early in their career, some slave for decades before finally solving the puzzle, others have several key moments, and for many architects this moment of perfection may never arrive – a sad fact that haunts such a theory focused and genius glorifying profession.

This concept of differing modes of achieving ‘genius’ is not isolated to just architecture, but nearly all fields ruled by the pursuit of innovation and disruption. If this topic interests you more deeply I would highly recommend listening to Malcolm Gladwell’s episode of Revisionist Histories podcast ‘Hallelujah’, which explores similar concepts in both music and fine art.

Vanna Venturi House, Robert Venturi, Chestnut Hill c.1964 [7]

Since the dawn of modernism in the early 20th century it ruled all progressive architectural theory. This was until the work of several aggressive young architects sought to disrupt this stronghold. One key character in this upheaval was Robert Venturi. He was a revered architectural academic who had exemplary understanding of design history and theory. He was disgruntled with the swathes of history and intricacy that had been rejected by the modernist movement, which was realized in the defining book ‘Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture’ in 1966.

“I like complexity and contradiction in Architecture. … Orthodox Modern architects have tended to recognize complexity insufficiently or inconsistently. In their attempt to break with tradition and start all over again, they idealized the private and elementary at the expense of the diverse and sophisticated.”

This defining piece of literature was a landmark piece of architectural theory that shaped the next phase of architecture. Venturi’s ideals where so vivid and energetic in this publication that it concurrently led to a built realisation - a house for his mother, the Vanna Venturi House in Chestnut Hill, c.1964. The Vanna Venturi house will forever sit on the architectural timeline as one of the most important built works of the last century due to the pivot that it prompted in the architectural discourse. The ability of his own writings to realise a distinct built form led to this project becoming one of the banner projects for postmodernism and one of the more important Thesis Houses built.

Venturi in designing this house engaged in a strong legacy of an architect completing their first projects for family. Architecture unlike other creative professions such as music and fine art cannot be realised without an amenable client. The built outcome is so heavily dictated by site, budget and brief that innate theoretical desires are often smothered in the pursuit of getting the project built. A project for a family member, especially a parent, is a fertile ground of shared upbringing and desires between both architect and client, that increases the chances of it becoming a seminal project in an architect’s career.

Vanna Venturi House, Robert Venturi, Chestnut Hill c.1964 [8]

My architecture travels unknowingly lead me to a series of varied Thesis Houses. All of these projects were different in both status and concepts, but collectively important in developing a greater understanding of the link between the architectural discourse and built outcomes.

Personally my architectural life is busily trying to exist between three modes: my professional role as a project lead at Richard Beard Architects in San Francisco, designing my mothers home back in Australia in my spare time and my extensive architectural travels and research. I find the Thesis House projects quite inspiring as I myself begin to start to rationalise my architectural understanding into built outcomes.

To architects and the public more generally, Thesis Houses stand as amazing pieces of history that need to be maintained, studied and enjoyed. We need to ensure their importance and the work of the architects behind them are embraced, acknowledged and grown, rather than forgotten.

Image Source:

Ash Street Perspective, World Architecture

Villa Savoye Model, MoMA

Ash Street Plan, Knoll

Trenton Bath House, louiskahn.org Photography: Arne Maasik

Richards Medical Research Laboratories, Wikipedia

Trenton Bath House Plan, Great Buildings

Vanna Venturi House, Curbed, Photographer: Matt Wargo

Vanna Venturi House, Ten Buildings, Photographer: Steven Goldblatt