March 2020

St John’s Abbey, Marcel Breuer, Collegeville MN, 1961 [1]

Marcel Breuer’s architectural career spanned numerous countries and continents. His portfolio had a significant influence on both his peers and future generations, as one of the most important architects of the 20th century. Breuer’s connections to several key forces of the modernist movement: the Bauhaus, Harvard GSD and postwar New York City, percolated and emboldened his discourse. His work was at the forefront of a scale shift in architecture as the industry was searching for a coherent strategy for the new era of high-rise buildings. His work, which encompassed furniture design, to mass housing, was pioneering in nature. This diversity in scale, design and public perceptions across his career, prompted this article to explore and understand his work more thoroughly.

Breuer was born in Hungary in 1902. As a teenager he moved to Vienna to study art and design. He soon found himself at the Bauhaus in Weimar, one of the most innovative and prominent design schools of its era. It was during his time at the Bauhaus, both as a student and also as master of the furniture workshop in Dessau, that Breuer formed an affinity for the lightweight, verging on weightless, in his innovative furniture designs.

Breuer moved to Berlin in 1928 where he attempted to translate his pursuit of lightness in furniture to architectural practice. This first came to fruition in his Harnischmacher House of 1932. This design consisted of a lightweight steel and reinforced concrete form hovering above the site in a way characteristic of Le Corbusier’s five points of a new architecture.

Harnischmacher House, Marcel Breuer, Wiesbaden, Germany, 1932 [2]

The Harnischmacher House expresses the influence of the Bauhaus ‘Vorkurs’ preliminary course. This program focused on the research of contrasting textures, forms, materials and patterns of perception to formulate a method of making that was freed of the need to form a composition, instead prioritising the methods of making. Breuer most notably adopted from these teachings a strong appreciation for contrasts, which he expressed throughout his design career with the prominent use of open and closed, and imbedded and projected.

During WWII the house was destroyed and sadly has been largely forgotten from the canons of early international style design. This most likely would have greatly changed if the house were completed slightly earlier and had the opportunity to be included in Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s defining International Style exhibition and subsequent catalogue for MoMA in 1932. Nonetheless, Breuer’s ability to concisely synthesise the varying influences in his life was a precursor to the way in which Breuer’s design ethos was able to evolve as positive influences intersected along the path of his career.

Gane Pavilion, Marcel Breuer, Bristol, England, 1936 [3]

As the heat of WWII intensified in the 1930’s, Breuer moved to the calmer setting of England. It was in this new location that Breuer once again appropriated his surroundings. This time it was the vernacular heavy fieldstone wall. He began to collage the rustic mass of England with the lightness of Corbusier’s modernist ideals. This realised itself in the design of the Gane Pavilion and also later in the residential designs Breuer is better known for in the United States.

As Hitler’s regime intensified Breuer, a Jewish born Hungarian, began to find Europe untenable. In 1938 Breuer accepted a role at Harvard in the USA, at the insistence of Walter Gropius, who he had previously worked under at the Bauhaus. In collaboration with Gropius once again, Breuer was able to start developing a portfolio of private residential projects across New England that became the bedrock for his long and successful career.

Hagerty House, Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, Cohassett MA, 1938 [4]

Breuer’s work in the US continued to explore the important relationship between the authenticities of vernacular regional design in collaboration with the growing impetus of modernism. This deliberate balance of opposites linked back to his Bauhaus tuition. The earliest examples of these houses included the Hagerty House, c.1938, the Gropius House, c.1938 and his own Breuer House, c.1939, all of which were co-authored with Gropius. In these houses Breuer adopted the lightweight American balloon framed construction and contrasted it with the elements he had inherited along his journey: heavy walls of fieldstone and the modernist characteristics of hovering and cantilevered forms. This synthesis of varied influences created houses that continue to have lasting appeal.

“The house [Chamberlain Cottage, c.1942] represents the modern transformation of the original American wooden building. It was only one large room and a kitchen and bath, but in my opinion it was the most important of all [of my house designs], and had perhaps the greatest influence on the development of American architecture.”

Breuer’s explorations in residential design continued to be refined as he developed a greater understanding for the vernacular language of American design and how this could be manipulated to accommodate other influences. The Chamberlain Cottage marked a key moment in the progression of his career. It was the last single family home that Breuer would design in collaboration with Gropius and it is a clear evolution of their collaborations. The small cottage has a very minimal design that is able to create great warmth and texture without the typical layerings of US residential design. Breuer at Chamberlain Cottage has able to develop a newfound ability to transform the wood frame structure through a textured, minimal design approach. This design was a defining design moment in his career due to its distinct divergence from both Gropius and the direct influences of New England regional design.

Chamberlain Cottage, Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, Wayland MA, 1941 [5]

Breuer’s career found new momentum after Chamberlain Cottage, a path that would detach him from both Gropius and New England, prompting a move to New York City in 1946. His rise as a designer of note was formalised when he was selected to design and exhibit one of three houses situated in the garden courtyard of MoMA. This design allowed Breuer to affirm the theories inherent in the Chamberlain Cottage and exhibit on the world stage a design that at once felt grounded by vernacular earthiness, minimal wooden warmth and the energy of the modernist movement.

House in the Garden, Marcel Breuer, MoMA, New York, 1949 {6}

This early portfolio of refined and articulate private residential work quickly crowned Breuer as one the designers best positioned to embrace the postwar boom, not only in New York, where his newly opened office was located, but also across the US and the modernising world in general.

Breuer’s office grew dramatically after the MoMA exhibition. Interestingly though this growth was not driven by private residential commissions, but from two large-scale projects that would forever shift his practice and design aesthetic. The two projects, which both arrived in his office in 1953, were the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris and the St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota. The initial humbly sized New York office, quickly expanded to a large office on several floors of a Madison Avenue office building.

The world was at a transition point coming out of the Second World War, with the workforce transitioning from being largely hands based, to an increasingly administrative one. This was also coupled with the rise of large corporations and universities that were looking to mark their growth with substantial buildings to house their operations and advertise their growing presence. The arrival of these two projects in 1953 was situated Breuer perfectly to be at the forefront of defining what this next era of architectural design would entail.

UNESCO Secretariat Building, Marcel Breuer, Paris, 1958 [7]

The UNESCO Headquarters in Paris was designed as an international collaboration of esteemed architects, in a new era of democratic design. The initial design team encompassed a range of internationally prominent architects, including the esteemed names Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, as well as Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Lucio Costa and structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi. A protracted collaborative design process eventually settled on a smaller design team of Breuer, with the Italian engineer Pier Luigi Nervi and French architect Bernard Zehrfuss, the team was commonly known as BNZ. On top of this complicated design process that at times encompassed up to ten strongly opinions architects, the project had three separate schemes and two separate potential sites, which took a lot of angst to untangle.

The final design of the UNESCO complex encompassed a series of concrete buildings. The largest of the buildings was the Secretariat, a seven storey office building, laid out as a Y-shaped building, floating above the plaza on sculptural concrete piers. The other main building, the Conference Building, was a trapezoid building in plan, which is formed by a dynamic series of folded-plate concrete structural walls.

Breuer’s collaboration with Nervi would unlock innovative and influential results for both this project and the subsequent path of his career. Nervi in the decade before the UNESCO commission was experimenting with reinforced concrete. He was exploring, much like Breuer was with plywood, how the positioning of planes in alternating orientations created unprecedented material strength and unlocked much thinner, lighter and sculpted concrete forms. The BNZ team through the development of the contrasting Secretariat and Conference buildings were exploring how a concrete exoskeleton could be boldly expressive and functional – an intentional contrast to the Chicago steel framed skyscrapers or the traditional American balloon frame.

UNESCO Conference Building, Marcel Breuer, Paris, 1958 [8]

The UNESCO complex in Paris was designed at a pivotal point in the architectural discourse, as the concerns over the suitability of modernism had started to permeate. Breuer felt that the Chicago style of glass skyscrapers, was an inappropriate functional solution for high rise developments due to its inability to synthesise the integration of the growing technological age. He especially thought this was the case for the growing institution typology, who were seeking a form of monumentality distinct from the International Style preferred by corporations. To solve this conundrum Breuer searched for a way to translate the success of his houses into a successful design strategy. A potential solution appeared through his collaboration with Nervi at UNESCO. Nervi’s masterful sculpting of structural concrete, allowed the hand of the artist to once again be realised at a fundamental level within the design. Breuer thought that this new use of concrete harked back to gothic architecture, where the way the weight was supported structurally, also became an intrinsic part of the design aesthetic.

The completion of the UNESCO buildings marked a defining point in Breuer’s career. The design looked to rethink the relationship of structure and design by once again creating a synthesis between the two. The project is an exploration of the contrasts and affinities of reinforced concrete through the varying uses of bending and folding. The design due to its bureaucratic design process and prototypical nature is not perfect. The project took risks and trialed previously untested processes that generated a rich design dialogue going forward that had an indelible impact on Breuer’s career and legacy.

St John’s Abbey, Marcel Breuer, Collegeville MN, 1961 [9]

While Breuer was busy trying to untangle the bureaucratic design process in Paris, he was simultaneously developing a design for the St John’s Abbey, a project to rebuild one of the largest Benedictine abbeys in the world, in Collegeville, Minnesota. For this design process, unlike at UNESCO, Breuer was the sole lead designer and was able to refine his concepts with clarity. Over a series of years Breuer would design nineteen buildings at St John’s, with the abbey church and monastery becoming iconic examples of the new style Breuer was developing in close collaboration with Nervi. Breuer was selected for the commission as the church felt that his inclination for functional designs, rich with an honest use of materials, suited Catholicism’s desire to think boldly and realise these notions in a manner that would thrive for many centuries to come.

Given the concurrent nature of St John’s and UNESCO there is a strong conceptual link between the two projects. Nervi’s advice was sought for the Abbey and the layout soon had a clear correlation with the Conference Building at UNESCO. Breuer implemented many of the successful features from the Conference Building in an effort to create the monks desire for a transformed modern space of worship.

“Concrete can reflect the stresses working in the structure with photographic truthfulness.”

The Abbey continues the strong use of folded concrete forms with twelve buttress-like walls flanking the sides of the nave and carrying up and over the congregation seated below. These folded planes increase in scale as they engage with the broader span of the bell shaped plan – further reinforcing the honesty of the form to its structural role. This pattern of diagonals give the space a dynamism and movement that focused attention down towards the altar. Nervi’s input created the key structural gestures that defined the space. However, at the St John’s Abbey, Breuer also utilized his Bauhaus educational cues to incorporate a textural richness that Nervi often looked to avoid in favour of structural smoothness. Breuer was able to build upon Nervi’s structural logic with a modernist collage of elements, most notably the exterior banner and honeycomb front façade that transformed the project into an ethereal modernist creation.

St John’s Abbey, Marcel Breuer, Collegeville MN, 1961 [10]

These two institutional projects propelled Breuer’s career to an international level. Through the execution of these two projects, even with the varied UNESCO reviews, it positioned Breuer as one of the leading designers for new institutional buildings, a defining typology of the era. Breuer’s success was in his ability to characterise a type of monumentality, one that was able to be modern and textured, without falling into the use of historic diatribe and empty symbols.

Breuer was able to formalise this developing niche of design soon after, with his most notable and iconic design, the Whitney Museum of American Art. In this project his transformation from the designer of humble, lightweight vernacular houses, into the sculptor of textured, heavy institutional projects was ratified. The design was a culmination of Breuer’s research and experiments from the preceding decades.

Whitney Museum of American Art, Marcel Breuer, New York City, 1966 [11]

The Whitney Museum trustees decided in 1963 to shift away from their mid-town location and establish a new image in the growing gallery scene of the Upper East Side. The interview process included the distinguished names of I.M. Pei, Louis Kahn and Philip Johnson. The trustees ultimately felt that Breuer was the best selection to reposition their American art both in New York and internationally.

Breuer’s design encompassed an inverted ziggurat, finished in dark grey granite that looms over the corner of Madison Avenue. The success of the building lies in its concurrent sensations of suspension and massiveness – achieved through the hovering of gigantic mass. A direct link to Breuer’s early Bauhaus furniture studies of levitating and his fantasy of creating a chair that allowed the user to be sitting on air. Here, instead of bended metal tube chairs, it is a dramatically top heavy building mass that floats over an open lobby space below. This mass is both hovering over the entry bridge and heavily grounded to the rear of the site, creating a level of dynamism that distinctly evolves from the energy Nervi’s buttress walls.

Whitney Museum of American Art, Marcel Breuer, New York City, 1966 [12]

Breuer’s design has aware of the associations of the thriving advertising scene along Madison Avenue. The building is intentionally differentiated from this commercial greed that was being defined by the glass towers of the International Style. The Whitney Museum contrasted this with its dark granite façade, an uncommon New York material, as well as through its form that is instantly recognisable – a substantial diversion from the uniformity of the commercial skyscrapers.

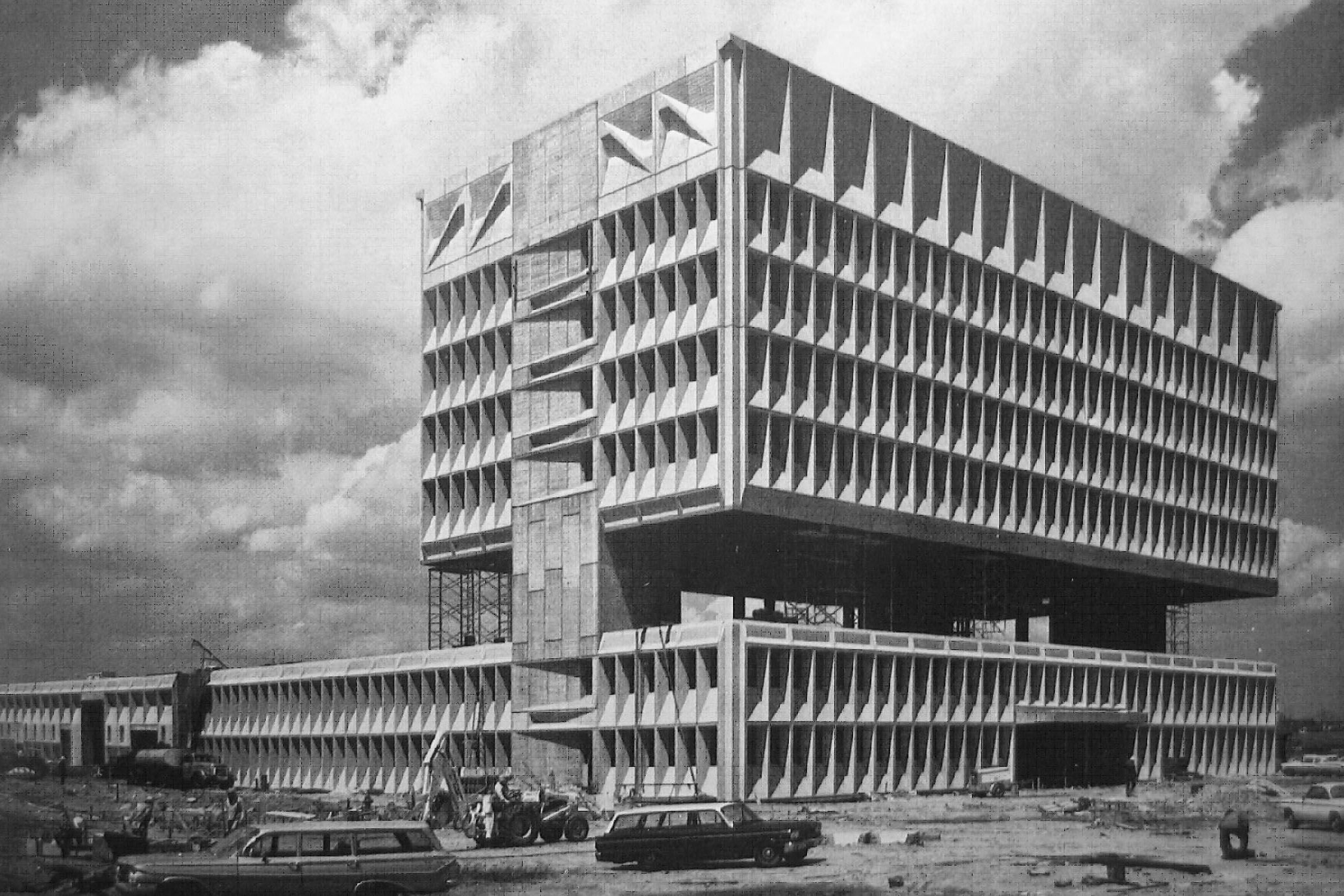

The success of the Whitney Museum gave Breuer the prominence to explore his evolving design concepts with relative freedom. The phase after the Whitney is characterised by heavy massing and repeating deeply sculpted precast concrete window units. One building that best defines this next phase in Breuer’s career is the Armstrong Rubber Company building in New Haven. This project became one of his most notable projects for its distinctive form and position on the Interstate 95 between New York and Boston.

Armstrong Rubber Building, Marcel Breuer, New Haven [13}

The Armstrong Rubber Building consisted of a low sprawling research building that has an office tower propelled above it, with a distinctive two storey air gap separating the lower and upper portions. This decision achieved the clients desire for height in an iconic manner, through thrusting the upper portion towards the roadway like a billboard. A key facet of both the upper and lower forms, is the modular precast window units. Breuer’s later projects would continue to refine this system as an intrinsic part of his creation of institutional monumentality.

“Concrete allows the architect three dimensions; he can design elevations moving in and out, he can create depth in a façade, he can become a master in this ‘new baroque’.”

Breuer’s ‘New Baroque’ was focused on the way structural concrete could be sculpted to transform the emotional effects of the project – especially how the structural effects were displayed. Nowhere did Breuer better synthesise these concepts than in the IBM France Research Center project in La Gaude. Here Breuer was able to master the two key items of his late career: fluidly shaped pilotis and deeply sculpted concrete façade.

IBM France Research Center, Marcel Breuer, La Gaude, France [14]

As Breuer’s career progressed his desire to amplify the plastic properties of concrete gave him a set of tools that he was able to execute in various ways across La Gaude. This artistic use of concrete is best demonstrated in the tree-like, massive piloti’s that levitate the upper portion of the building. Breuer refined and reused these elements excitedly as he felt that concrete had the unique ability to be moulded to express the builder’s thoughts precisely.

“Technology, rather than endangering the artist, fuses him with the engineer, with the scientist.”

The defining achievement of La Gaude was the mastery of the precast concrete façade panel. This was an element that had been evolving in earlier projects with success. However at La Gaide, Breuer developed this element to be much more than a textured façade that controlled sun and shade, as in Le Corbusier’s previous experiments with the brise soleil. Instead the precast panels became a tectonic expression of both the interior and exterior requirements of the façade. The walls were integrated with all the technical, mechanical and environmental requirements of the interior spaces to create a sculptural modular façade.

The end result of this exploration was a window wall that provided a new depth of façade, one where the fundamental needs of the building are intrinsically incorporated in the mass of the exterior envelope. This refinement of the heavy concrete façade broke away from the predominant glass and steel curtain wall construction, which Breuer felt was at odds with the rise of technological systems. This evolution at La Gaude, and other projects of that period? gave Breuer a strategy for achieving a monumental institutional form in the postwar era.

Breuer at this time had a fully functioning office in France and was completing several other significant commissions in the country. One of these was a mass housing project in Bayonne, known as ZUP de Sainte-Croix. This project was at the tail end of a large national project to meet housing shortage issues. The Bayonne project’s scale was quite immense and commanded a prominent ridge looking over the town. The project began with great optimism, as Breuer was one of very few non-French architects selected as part of the scheme. However, as the project progressed and neared completion, the ideals that underpinned the whole mass housing scheme became to feel ill-fated.

Unfortunately for Breuer the project in Bayonne was being constructed as a growing unease about modern architecture was starting to proliferate. In France especially there began to be a direct public association between modern architecture and the alienating effects of state capitalism. This lead to a situation where by the end of the 1970’s projects similar to Breuer’s, in the housing scheme, were already being demolished. Breuer’s project with its position proudly on the hill began to be perceived by the township as an attack on the landscape of Bayonne. The project survived several attempts for demolition and was renovated between 2007 and 2013, amid a rejuvenated appreciation for the project.

The growing negativity to the perceived harshness of Brutalism, a term long associated with Breuer’s later works, significantly hurt Breuer’s position in the architectural discourse, as postmodernism began to appear as the rebuttal to the extremes of modernism. The peak example of this was the proposed, but unbuilt, addition to the Whitney Museum by Michael Graves.

Unbuilt proposal for the extension of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Michael Graves, 1981 [15]

Breuer’s legacy took a significant hit during the rise of the postmodernist movement. As postmodernism became the preferred style of design the architectural community split into two camps. One, which focused further inside the architectural discourse for motivation – best characterised by Peter Eisenman. The other looked beyond architecture to explore concepts of popular culture and iconography – best characterised by Robert Venturi. Breuer’s design concepts did not fit neatly into either of these factions, causing him to be sidelined as this new design style became popular.

In recent years, with a renewed fondness for mid-century design sweeping the globe, the work of Breuer is once again being popularised. This renewed awareness started with Breuer’s oldest work, his bent metal tube chairs, which have almost become a ubiquitous part of modern interiors. This interest in his chairs also renewed discussions around his buildings and their agendas, allowing these buildings to once again be an important part of the architectural discussion.

Cesca Chair, Marcel Breuer, 1930 [16]

The revitalised perspective of Breuer’s work has also been enhanced by the opening of the Marcel Breuer Digital Archive as part of the Special Collections Research Centre at Syracuse University. This groundbreaking project has collated and digitised all of Breuer’s drawings, photos, papers and correspondence onto an online portal that has dramatically improved the ability to research and understand Breuer’s work. This has already lead to several books that have revitalised the ability to get access to the inner workings of his career.

Marcel Breuer retired from his firm in 1976 and passed away in 1981 at the age of 79, just weeks before a major show on his work opened at the Museum of Modern Art. Breuer’s career intertwined with some of the most pivotal influencers of the 20th century, allowing his career to play a key part in both early residential modernism and the late modernist search for a monumental language for institutional projects. His project’s are a key part of the architectural discourse that should be valued for the ability to understand and evolve vernacular design with a strong sense of structure, function and texture. He is one of the important figures of 20th century design and it is pleasing to see that the enthusiasm for his work is once again pushing his questions into contemporary design.

image Sources:

St John’s Abbey, Arquituraviva

Harnischmacher House, Places Journal

Gane Pavilion, Medium

Hagerty House, Dwell

Chamberlain Cottage, Dwell, Photo: Ezra Stoller

House in the Garden, Sotheby's, Photo: Ezra Stoller

UNESCO Secretariat Building, Alchetron

UNESCO Conference Building, Scandinavian Collectors

St John’s Abbey, Places Journal

St John’s Abbey, Places Journal

Whitney Museum of American Art, Architectural Digest

Whitney Museum of American Art, Beyer Blinder Belle, Photo: Ezra Stoller

Armstrong Rubber Building, Research Gate

IBM France Research Center, Design Inspiration

Unbuilt proposal for the extension of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Metropolis Mag

Cesca Chair, Knoll